Estate Tax in the United States: An Overview

The estate tax in the United States is a tax levied on the transfer of property and assets upon the death of a taxpayer. Also known as the “death tax” or “inheritance tax,” it is designed to target the wealthiest individuals and estates, preventing the concentration of wealth across generations. The tax is applied to the total value of the deceased’s assets, including real estate, stocks, bonds, and other investments, minus any applicable deductions and exemptions.

Currently, the estate tax exemption limit in the United States is set at $11.7 million per individual and $23.4 million per couple for 2021. Estates valued below these thresholds are not subject to federal estate tax. The top estate tax rate is 40%, which applies to the portion of an estate’s value exceeding the exemption limit.

History and Evolution of Estate Tax in the US

The estate tax in the United States has a rich history dating back to the early 20th century. The modern estate tax was first introduced in 1916, during the presidency of Woodrow Wilson, as a means to generate revenue for the federal government during World War I. The tax initially applied to estates valued at $50,000 or more, with a top rate of 10%. Over time, the exemption limit and tax rates have fluctuated significantly, reflecting changing economic conditions and political priorities.

Throughout the years, the estate tax has undergone several significant reforms. In 1976, the Tax Reform Act simplified the estate tax structure and introduced the unified credit, allowing a portion of an estate to pass tax-free to the next generation. In 2001, the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act gradually increased the exemption limit and reduced the top tax rate, culminating in a temporary repeal of the estate tax in 2010. However, the tax was reinstated in 2011 under the Tax Relief, Unemployment Insurance Reauthorization, and Job Creation Act, with a $5 million exemption limit and a top rate of 35%.

Most recently, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 further increased the estate tax exemption limit to $11.18 million per individual and $22.36 million per couple, indexed for inflation. The top estate tax rate remains at 40%. With these changes, the number of estates subject to the estate tax has significantly decreased, making it a less pressing concern for many American families.

Calculating Estate Tax: A Step-by-Step Guide

Calculating the estate tax in the United States involves several steps, including determining the taxable estate, applying deductions and exemptions, and calculating the tax owed. The following is a simplified guide to help readers understand the process:

-

Determine the taxable estate: The taxable estate is calculated by adding the fair market value of all assets owned by the deceased at the time of death, including real estate, bank accounts, investments, retirement accounts, life insurance policies, and personal property. Subtract any debts, funeral expenses, and administrative expenses to arrive at the taxable estate.

-

Apply deductions: Several deductions can be applied to reduce the taxable estate, such as marital deductions, charitable deductions, and administrative expenses. Marital deductions allow the entire estate to pass to the surviving spouse tax-free, while charitable deductions allow for a reduction in the taxable estate based on the value of donations made to qualified charitable organizations.

-

Calculate the applicable exemption: The applicable exemption is the amount that can be subtracted from the taxable estate before calculating the estate tax. As of 2021, the exemption limit is $11.7 million per individual and $23.4 million per couple. Estates valued below these thresholds are not subject to federal estate tax.

-

Calculate the estate tax: Once the taxable estate has been reduced by deductions and the applicable exemption, the estate tax can be calculated using the tax tables provided by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). The top estate tax rate is currently 40%, which applies to the portion of the taxable estate exceeding the exemption limit.

It is important to note that estate tax laws and regulations are complex and subject to change. Seeking the advice of a qualified estate planning professional is highly recommended to ensure accurate calculations and compliance with all applicable rules and regulations.

How to Minimize Estate Tax: Strategies and Tips

Individuals seeking to minimize their estate tax liability can employ various strategies and tips to preserve their wealth for future generations. Some of these methods include:

-

Gifting: The IRS allows individuals to give up to a certain amount per year without incurring any gift tax liability. In 2021, the annual gift tax exclusion is $15,000 per recipient. By gifting assets to family members or other beneficiaries during their lifetime, individuals can reduce the size of their taxable estate.

-

Trusts: Various types of trusts can be used to minimize estate tax liability, such as irrevocable life insurance trusts, grantor retained annuity trusts, and qualified personal residence trusts. These trusts can help remove assets from the taxable estate, provide tax benefits, and offer control over how assets are distributed.

-

Business succession planning: For business owners, implementing a well-designed succession plan can help minimize estate tax liability and ensure the continuity of the business. Strategies may include gifting ownership interests, selling the business to a family member or employee, or establishing a buy-sell agreement.

-

Charitable giving: Donating to qualified charitable organizations can provide significant estate tax savings, as well as income tax benefits. Individuals can choose from various charitable giving vehicles, such as charitable remainder trusts, charitable lead trusts, and donor-advised funds.

-

Lifetime estate tax planning: Engaging in comprehensive estate tax planning during one’s lifetime can help minimize estate tax liability and ensure that assets are distributed according to the individual’s wishes. This may involve working with a qualified estate planning professional to develop a customized plan tailored to the individual’s unique circumstances and goals.

By implementing these strategies and tips, individuals can effectively minimize their estate tax liability and preserve their wealth for future generations. However, it is essential to consult with a qualified estate planning professional to ensure that all applicable rules and regulations are followed and that the chosen strategies align with the individual’s overall financial and estate planning objectives.

State-Specific Estate Tax Rules and Regulations

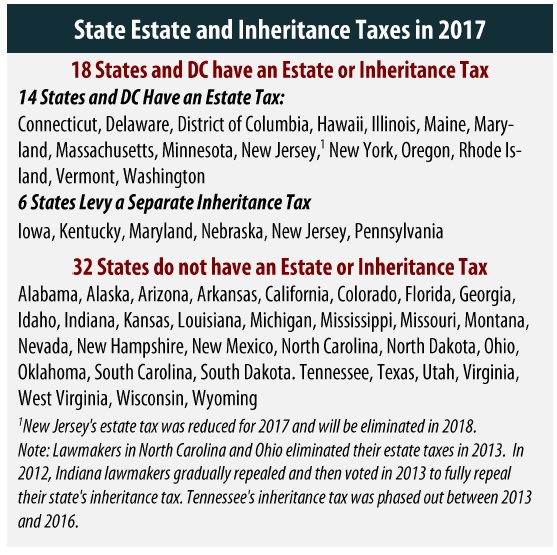

In addition to the federal estate tax, many states in the United States impose their own estate tax or inheritance tax. Understanding the unique rules and regulations of each state is crucial for individuals with significant assets or property in multiple states. The following is an overview of the key differences among various states regarding estate tax:

-

States with an estate tax: As of 2021, 12 states and the District of Columbia impose an estate tax, with exemption limits ranging from $1 million to $11.7 million. These states include Connecticut, Hawaii, Illinois, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New York, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont, Washington, and the District of Columbia.

-

States with an inheritance tax: Six states impose an inheritance tax, which is levied on the beneficiaries of an estate rather than the estate itself. These states include Iowa, Kentucky, Maryland, Nebraska, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. Exemption limits and tax rates vary by state and by the relationship between the decedent and the beneficiary.

-

States with no estate or inheritance tax: The majority of states do not impose an estate tax or inheritance tax, including Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Indiana, Kansas, Louisiana, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Mexico, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Virginia, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

It is essential to consult with a qualified estate planning professional to ensure that all applicable state and federal estate tax rules and regulations are followed. A well-designed estate plan can help minimize estate tax liability, preserve wealth, and ensure that assets are distributed according to the individual’s wishes.

Estate Tax vs. Income Tax: Key Differences

Estate tax and income tax are two distinct types of taxes that serve different purposes in the United States tax system. Understanding the key differences between these two taxes can help taxpayers better plan their financial and estate planning strategies.

-

Purpose: Estate tax is a tax on the transfer of property and assets upon a taxpayer’s death, while income tax is a tax on the earnings and income of individuals and businesses. Estate tax is designed to prevent the concentration of wealth across generations, while income tax is used to fund government programs and services.

-

Exemption limits: Estate tax and income tax have different exemption limits. As of 2021, the federal estate tax exemption limit is $11.7 million per individual, while the income tax exemption for single filers is $12,550 and $25,100 for married filing jointly. These limits are subject to change over time and may vary by state.

-

Tax rates: Estate tax and income tax also have different tax rates. The federal estate tax top rate is 40%, while the income tax top rate for individuals is 37% as of 2021. State income tax rates vary, with some states having no income tax and others having top rates ranging from 3% to 13.3%.

-

Deductibility: Estate tax deductions and exemptions can help reduce the taxable estate, while income tax deductions and credits can help reduce taxable income. Estate tax deductions may include marital deductions, charitable deductions, and administrative expenses, while income tax deductions may include business expenses, charitable contributions, and mortgage interest.

By understanding the key differences between estate tax and income tax, taxpayers can better plan their financial and estate planning strategies and minimize their tax liability. Consulting with a qualified tax or estate planning professional is recommended to ensure compliance with all applicable rules and regulations.

Navigating Estate Tax Returns and Reporting Obligations

Navigating estate tax returns and reporting obligations can be a complex and time-consuming process. However, understanding the forms and processes involved can help taxpayers fulfill their obligations accurately and efficiently.

-

Estate Tax Return (Form 706): The Estate Tax Return, or Form 706, is used to report the value of the deceased’s gross estate and any taxable gifts made during their lifetime. The form is due nine months after the date of death, with a six-month extension available upon request. The executor or personal representative of the estate is responsible for filing the return and paying any estate tax due.

-

Generation-Skipping Transfer Tax Return (Form 709): The Generation-Skipping Transfer Tax Return, or Form 709, is used to report transfers made to beneficiaries who are more than one generation below the transferor, such as grandchildren or great-grandchildren. The form is due on April 15th of the year following the transfer, with a six-month extension available upon request.

-

Fiduciary Income Tax Return (Form 1041): The Fiduciary Income Tax Return, or Form 1041, is used to report income earned by the estate or trust during the tax year. The form is due on April 15th of the year following the tax year, with a six-month extension available upon request.

-

Estate Tax Closing Letter: After the estate tax return has been filed and any tax due has been paid, the IRS will issue an Estate Tax Closing Letter. The closing letter confirms that the estate tax return has been accepted and that no further action is required, unless additional information is requested by the IRS.

Consulting with a qualified tax or estate planning professional can help taxpayers navigate the complex estate tax return and reporting obligations. A well-designed estate plan can help minimize estate tax liability, ensure compliance with all applicable rules and regulations, and provide peace of mind for taxpayers and their beneficiaries.

The Future of Estate Tax in the United States

The estate tax in the United States has undergone significant changes and reforms over time, and its future remains uncertain. Political and economic factors can influence the trajectory of estate tax policy, potentially impacting taxpayers and their beneficiaries.

-

Potential changes: Proposed changes to estate tax policy may include lowering the exemption limit, increasing the tax rate, or eliminating the tax altogether. These changes could have significant implications for taxpayers and their heirs, potentially reducing the amount of wealth transferred across generations or increasing the tax burden on estates.

-

Economic factors: Economic factors, such as inflation, economic growth, and budget deficits, can also impact estate tax policy. For example, a growing economy may generate higher tax revenues, reducing the need for estate tax revenue. Conversely, a struggling economy may necessitate higher tax revenues, potentially leading to an increase in the estate tax rate or a reduction in the exemption limit.

-

Political factors: Political factors, such as changes in administration, shifts in political power, and public opinion, can also influence estate tax policy. For example, a change in administration may lead to a different approach to estate tax policy, potentially resulting in significant changes to the tax code.

While the future of estate tax in the United States remains uncertain, taxpayers can take proactive steps to minimize their estate tax liability and ensure compliance with all applicable rules and regulations. Consulting with a qualified tax or estate planning professional can help taxpayers navigate the complex estate tax landscape and provide peace of mind for themselves and their beneficiaries.